The invention of Bitcoin was a technological breakthrough that disrupted the status quo. When Bitcoin was first created, central banks thought they could safely ignore it.

As Bitcoin adoption gained momentum, central banks were forced to pay attention and try to understand what Bitcoin means for the roles of central banks and the technology they use.

In recent years, central banks have converged on the point of view that there are aspects of Bitcoin that they can and should incorporate into their processes and underlying software.

CBDC (central bank digital currency) is a catch-all term for a central bank-issued currency that incorporates elements of cryptocurrencies into its operating model.

Since money is already digital, why are governments considering CDBCs

Central bankers and government officials claim CBDCs promote financial inclusion by offering the unbanked easy access to safe money.

They also state that CBDCs will increase payment efficiencies, lower transaction costs and make it easier for governments to enact monetary and fiscal policy.

In addition to these claims, CBDCs offer governments two benefits that should not be ignored – CBDCs increase the state’s financial power over citizens, and they serve as a surface-level competitor for private sector innovations like Bitcoin.

Implementing a CBDC risks destabilizing large sectors of the economy, which explains why people are uneasy about the idea in countries like the United States.

Further, they represent a mild technological upgrade to fiat money – not a breakthrough in monetary technology like Bitcoin.

CBDCs are still the same inflationary fiat currencies as before, albeit fully digital and less private.

In contrast, consumers are drawn to Bitcoin because of its unique monetary qualities and its censorship resistance.

Fortunately, CBDCs are not a threat to Bitcoin. In fact, CBDCs may even hasten Bitcoin’s adoption.

What are CBDCs

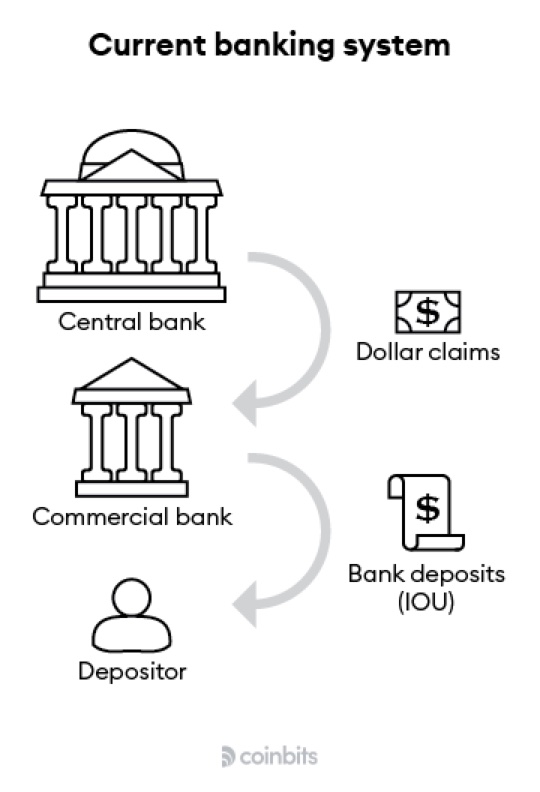

In the United States, the Federal Reserve creates dollars. These dollars consist of a mix of physical cash and reserve balances held by banks at the Fed.

Consumers use a combination of physical cash and digital dollars represented as deposits in their bank accounts.

However, digital dollars held in consumer bank accounts differ from those held by banks at the Federal Reserve.

Digital dollars in consumer bank accounts actually represent claims to dollars banks hold with the Fed.

Consumers cannot directly use these dollars because only financial institutions can access them.

We do not notice the difference between digital dollars – claims to reserve balances – and actual dollars because the US banking system is currently solvent and secure enough that the distinction has no day-to-day consequences – for now.

Pre-CBDC banking model in the US

CBDCs differ from digital dollars because they are actual dollars produced by the Fed, not claims to dollars held by banks at the Federal Reserve.

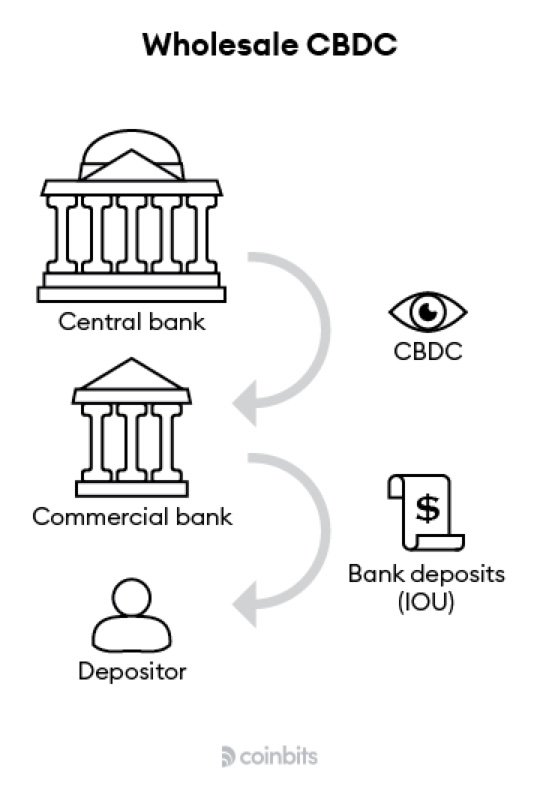

There are two avenues for central banks when implementing CBDCs – wholesale and retail.

Under a wholesale model, CBDCs emulate bank reserves. The CBDC would be the monetary good that is deposited in the accounts that banks and other financial institutions hold at the Federal Reserve.

Banks would then provide a representation of those dollars, likely rehypothecated, in consumer bank accounts.

Wholesale CDBC model

As Nik Bhatia describes in ‘Layered Money,’

“Central banks could issue a digital currency in the form of wholesale reserves, which would only be accessible to banks… The digital reserves option has the potential to modernize financial infrastructure for the banking system, but it won’t impact how society interacts with money.”

In contrast, retail CBDCs would serve as digital cash for consumers. Think of a FedWallet app that lets you spend CBDCs just like any other cryptocurrency.

While the wholesale model would not significantly change the status quo, the retail route would upend the mechanics of the current banking system.

Retail CBDC model

Differences between the retail and wholesale models matter. As illustrated above, with a retail CBDC, Americans would have a direct bank account with the Fed without commercial intermediaries.

Given the unpredictable impact a retail CBDC would have on the American banking system, the Federal Reserve is focused on developing a wholesale CBDC instead.

Contrasting with that approach, however, the Biden-Harris administration reported on the feasibility of a CBDC system in the US and suggested there may be a growing political appetite for retail CBDCs.

The report states that “all should be able to use the CBDC system” and “the CBDC system should expand equitable access to the financial system.”

Since the wholesale model does not expand access to the financial system, the Biden-Harris report signals that politicians intend to explore the retail option.

CBDCs face problems

Business lending

CBDCs face competing goals. An important function of commercial banks is directing funds toward investment projects through loans.

If CBDCs successfully divert funds from the private financial system, entrepreneurs risk losing access to capital as CBDCs crowd out traditional banks.

Therefore, CBDCs would either compel governments to assume the lending role of commercial banks or reduce businesses’ access to capital.

Further, governments are ill-equipped to make investment decisions. When they do, the economy is impeded at best and severely damaged at worst.

Academics provide a solution to this problem of directing investment in an economy run on a retail CBDC, namely, to offer low CBDC interest rates to disincentivize large-scale CBDC accumulation.

However, this raises a question – if citizens must be disincentivized from using CBDCs for one of the key use cases for money, why introduce them? The answer is unclear.

This inherent contradiction might explain why over two-thirds of public comment letters in response to the Federal Reserve’s proposal for a CBDC view the idea negatively.

Privacy

By removing commercial banks as financial mediators, CBDCs offer governments exclusive control over each citizen’s bank account.

Government officials no longer have to work with commercial banks – they can limit, censor or stop financial transactions for any reason.

This is why CBDCs raise red flags for privacy-minded individuals.

Today, in China, DCEP (Digital Currency/Electronic Payments) allows the People’s Bank of China to surveil citizens’ everyday transactions.

Combining the DCEP with China’s social credit system gives the government the power to interact directly with consumer bank accounts based on political preference.

Even in Canada, which is not overtly authoritarian, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau froze the bank accounts of people who participated in – or even financially supported – protests against mandated COVID-19 vaccinations.

The programmability of CBDCs is also concerning. They allow central bankers to program monetary policy directly into the money people use every day.

For example, facing an economic crisis, central banks could decide to change the code for dollars so that they expire if they aren’t spent within an allotted time frame, forcing people to spend them on consumption to ‘stimulate’ the economy.

Government officials seem to be unaware of these risks or at least unwilling to discuss them. Instead, CBDC proponents praise their potential for programmability and surveillance.

Even putting aside privacy drawbacks, the consumer case for CBDCs is unclear. They do not alleviate financial problems, such as inflation, nor do they promote financial inclusion.

They also do not represent a technological breakthrough because the mix of technologies that they rely upon is already utilized by the Bitcoin network.

As William Luther and Andrew Bailey note,

“The standard case for a CBDC rests on the mistaken idea that we need new digital money for our new digital world. Much of our money is already digital though – commercial bank deposits and transfers are recorded on computers, not paper ledgers.”

Bitcoin –still better, not going away

In ‘American Banker,’ Rob Blackwell describes the threat this way,

“If bankers are not careful, they may find themselves on the losing end as they watch the Fed create an alternative to federally insured deposits.”

One can assume the commercial banking lobby will oppose CBDCs in full force, introducing another hurdle.

Further, while commercial banks are generally unpopular with consumers, it is questionable whether consumers would prefer interacting with central banks – distant monolithic institutions that are all but guaranteed to have even worse customer service.

While central bankers write papers and pontificate about digital currency consumers do not want, Bitcoin adoption will continue for one reason – it is simply the best form of money ever invented.

CBDCs do not threaten Bitcoin. In fact, insofar as they introduce additional risk, uncertainty and privacy concerns to the current financial system, the advent of CBDCs may even fuel further adoption of Bitcoin.

David Waugh is a business development and communications specialist at Coinbits. He previously served as the managing editor at the American Institute for Economic Research.

Check Latest Headlines on HodlX

Follow Us on Twitter Facebook

Check out the Latest Industry Announcements

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed at The Daily Hodl are not investment advice. Investors should do their due diligence before making any high-risk investments in Bitcoin, cryptocurrency or digital assets. Please be advised that your transfers and trades are at your own risk, and any loses you may incur are your responsibility. The Daily Hodl does not recommend the buying or selling of any cryptocurrencies or digital assets, nor is The Daily Hodl an investment advisor. Please note that The Daily Hodl participates in affiliate marketing.

Generated Image: Midjourney

Credit: Source link